American Tapestry – Compositions of John Mackey

“American Tapestry – Compositions of John Mackey” as featured the July 13, 2020 episode of “Monday Night at the Symphony” on WRR 101. This broadcast is our April 11, 2017 performance from the Meyerson Symphony Center with guest Chris Martin, Principal Trumpet of the New York Philharmonic.

Program Notes

John Mackey was born in 1973 in New Philadelphia, Ohio, to a musical family, but—perhaps surprisingly for a composer—he never learned to play a musical instrument. Instead, his grandfather taught him how to read music at a very early age by playing with music composition software. Mackey grew up in Westerville, Ohio, composing on the Apple IIe Music Construction Set and moving on to music “games” on the Commodore 64. By his own report, he learned how complex musical works went together by transcribing classical score after classical score throughout his high school years. Not the typical teenager, but it did get him into the Cleveland Institute of Music and later the Juilliard School, alongside such other yet-to-be-knowns as Steven Bryant and Eric Whitacre.

He graduated from Juilliard in 1997 and began toiling in the field of classical composition, setting his sights on conquering the symphony orchestra world. The symphony orchestra world—notoriously clannish, insular, and hard to conquer—did not take much notice. In 2005, however, Mackey turned to band, re-orchestrating his 2003 symphonic work, Redline Tango, for wind ensemble, and his fortunes changed forever.

Hailed as a fresh and exciting new voice in band composition, Mackey’s Redline Tango won the American Bandmasters Association’ Ostwald Award honoring the year’s outstanding composition for band, and the San Francisco Classical Voice called it “a true dazzler.” It made John Mackey an ‘overnight’ success. Mackey explained his change of focus in a classic blog post, Even Tanglewood Has a Band:

“Band is loud. She’s not quite as pretty as Orchestra, and she’s a bit, shall we say, bigger boned, but . . . Band loves what you do. Whereas it was like pulling teeth to get Orchestra to look at your new music (and if she looked, she was generally not impressed, often comparing you unfavorably to one of her many exes—like Dvorak) Band thinks it’s awesome. Band tells you things like “you’re special and perfect and I’ll appreciate you and your music like Orchestra never has and never will. What is a Composer supposed to do?”

Mackey’s choice was to build his reputation on innovative, accessible, and challenging works band students and musicians of all ages enjoy playing.

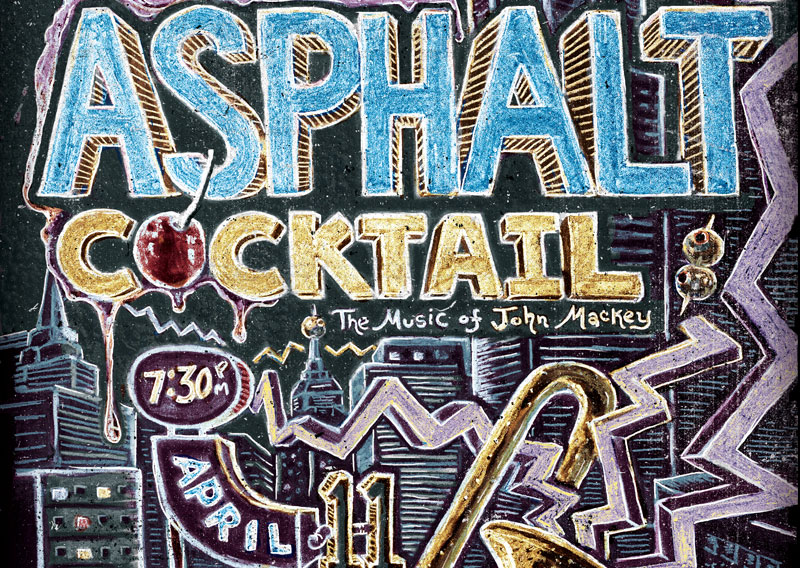

Asphalt Cocktail was commissioned by Howard J. Gourwitz as a gift to Dr. Kevin Sedatole, and premiered at the 2009 College Band Directors National Association conference in Austin. Of the work, Mackey said, “Asphalt Cocktail is a five-minute opener, designed to shout, from the opening measure, ‘We’re here.’ With biting trombones, blaring trumpets, and percussion dominated by cross-rhythms and back beats, it aims to capture the grit and aggression that I associate with the time I lived in New York. Picture the scariest NYC taxi ride you can imagine, with the cab skidding around turns as trucks bear down from all sides. Serve on the rocks.”

Mackey wrote Sheltering Sky in response to a commission from the Traughber and Thompson Junior High School Bands in Oswego, Illinois. The work begins slowly, with a gentle melody that touches base with several familiar folks songs, but isn’t quite any of them. The theme is, in fact, a Mackey original that only sounds like it ought to be a folk song. It builds to a climax that evokes wide open spaces and starlit skies, then comes to rest again, leaving the listener refreshed and relaxed.

When Mackey had the opportunity to write a trumpet concerto, he elected to move beyond creating a mere obstacle course for the soloist, and focused on saying something meaningful about the instrument itself and its resonances throughout history. The result is Antique Violences: Concerto for Trumpet.

As Mackey explains, “The title comes from a line in Rickey Laurentis’ Writing an Elegy, and reminds us that where there are humans, there is violence. So it is; so it has ever been. The concerto notes that, curiously, the trumpet and its cousins always call the bloody tune—so each movement considers a kind of violence through the lens of a historical style of music, closely associated with the trumpet.”

The concerto’s four movements carry the listener through a cycle of violence, from the ancient conflicts between countries and people. In the first, the structure of our social world is born and reborn, as kings draw new borders in blood. The second movement explores the more intimate violence that can exist in the home, while the third movement reflects the “sharp chasm of mourning.” Then, in the fourth movement, as grief turns to anger, the cycle begins again.

With Malice Toward None from Lincoln (encore)

Steven Spielberg’s 2012 historical epic focused on President Abraham Lincoln’s struggle to outlaw slavery before the Civil War ended—a tactic that ensured slavery would not return as Confederate states rejoined the Union. To score a film about both a vital issue and a towering historical figure, Williams drew on early American folk music, fiddle tunes, and battlefield trumpet calls to evoke an era where the highest ideals of our nation were defended by bare-knuckle politics. He recorded the score with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Christopher Martin, the CSO’s principal trumpet at that time, performed the haunting trumpet solo in With Malice Toward None for the soundtrack, and returns to join the Dallas Winds in this recording.

High Wire was commissioned by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Youth Wind Ensembles in honor of Thomas L. Dvorak, Founder and Music Director of the program. It was a work Mackey was eager to tackle.

“I was itching to write something fun and flashy and yes I suppose virtuosic for the ensemble,” Mackey recalled. “I had been writing slow, simple music just before, and my brain felt like a hyperactive dog that’s been locked up indoors for days. I needed to sprint around the yard, musically speaking. From the outset, I was just thinking ‘flashy

fanfare.’ To me a fanfare is a grand, brass-flourish-loaded opening gesture for a concert, but they’re usually very short. How could I create one that was four minutes long, keeping it exciting while not making it aurally exhausting?”

Sounds like something of a balancing act, but sure-footed Mackey manages not to fall.

This Cruel Moon is a new work that grew out of Mackey’s monumental 2014 composition, Wine Dark Sea: Symphony for Band, which, in turn was inspired by Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey. This work focuses on the story of Odysseus’ love affair with the nymph Kalypso. When Odysseus washes up on the shore of Kalypso’s island, she nurses him back to health and they become lovers. Yet, when Odysseus finally remembers his home, wife, and son after seven years, Kalypso weaves him a sail that will carry him back to them, even though it breaks her heart.

Mackey dedicated the source work to his wife, Abby, “without whom none of my music over the past ten years would exist.” Tonight’s performance is a world premiere.

There is a special moment each day, just after the sun sets, while a bit of light still lingers in the sky. It’s called the blue hour, and it’s a time when the heat and noise of the day begins to fade as we turn toward a quieter night. Mackey wrote his Hymn to a Blue Hour as a commissioned work for Mesa State College, one summer when he relocated from his home in Austin to an apartment in New York City. Of the work he said:

“I almost never write music ‘at the piano’; because I don’t have any piano technique. I can find chords, but I play piano like a bad typist types: badly. If I write the music using an instrument where I can barely get by, the result will be very different than if I sit at the computer and just throw a zillion notes at my sample library, all of which will be executed perfectly and at any dynamic level I ask. We spent the summer at an apartment in New York that had a nice upright piano. I don’t have a piano at home in Austin – only a digital keyboard – and it was very different to sit and write at a real piano with real pedals and a real action, and to do so in the middle of one of the most exciting and energetic (and loud) cities in America. The result – partially thanks to my lack of piano technique, and partially, I suspect, from a subconscious need to balance the noise and relentless energy of the city surrounding me at the time – is much simpler and lyrical music than I typically write.”

More and more frequently these days, new classical works are commissioned by a consortium of orchestras or university music programs. It’s a good system that keeps new music flowing, and pays the composer enough to keep body and soul together, while not costing any one member of the consortium too large a chunk of the budget. The Frozen Cathedral was commissioned by such a consortium, including the University of North Carolina, Greensboro; the University of Michigan; Michigan State University; University of Florida; Florida State University; University of Georgia; University of Oklahoma; Ohio State University; University of Kentucky; Arizona State University, and Metro State College.

John Locke, Director of Bands at University of North Carolina, Greensboro, led the collaboration with Mackey, and asked if Mackey would dedicate the work to the memory of Locke’s son, J. P. Locke, who had a particular fascination with Alaska and Denali National Park. Mackey agreed, but said:

How does one write a concert closer, making it joyous and exciting and celebratory, while also acknowledging, at least to myself, that this piece is rooted in unimaginable loss: The death of a child?

The other challenge was connecting the piece to Alaska – a place I’d never seen in person. I kept thinking about all of this in literal terms, and I just wasn’t getting anywhere. My wife, who titles all of my pieces, said I should focus on what it is that draws people to these places. People go to the mountains—these monumental, remote, ethereal and awesome parts of the world—as a kind of pilgrimage. It’s a search for the sublime, for transcendence. A great mountain is like a church. “Call it The Frozen Cathedral,” she said.

I clearly married up.

Many of the works on tonight’s program will be included in a new Dallas Winds recording that will set the standard for bands—and symphony orchestras—that play Mackey’s music for generations to come.

The Ringmaster’s March (encore)

John Mackey called this work “a riotous Ivesian circus parade; a joyful noise in honor of a man who has always been at the center of the show.” He also explains it, “Imagine if Charles Ives and I got drunk together and re-wrote Henry Fillmore’s The Circus Bee.” This one you’ve got to hear for yourself.

–Program notes by Gigi Sherrell Norwood