Program

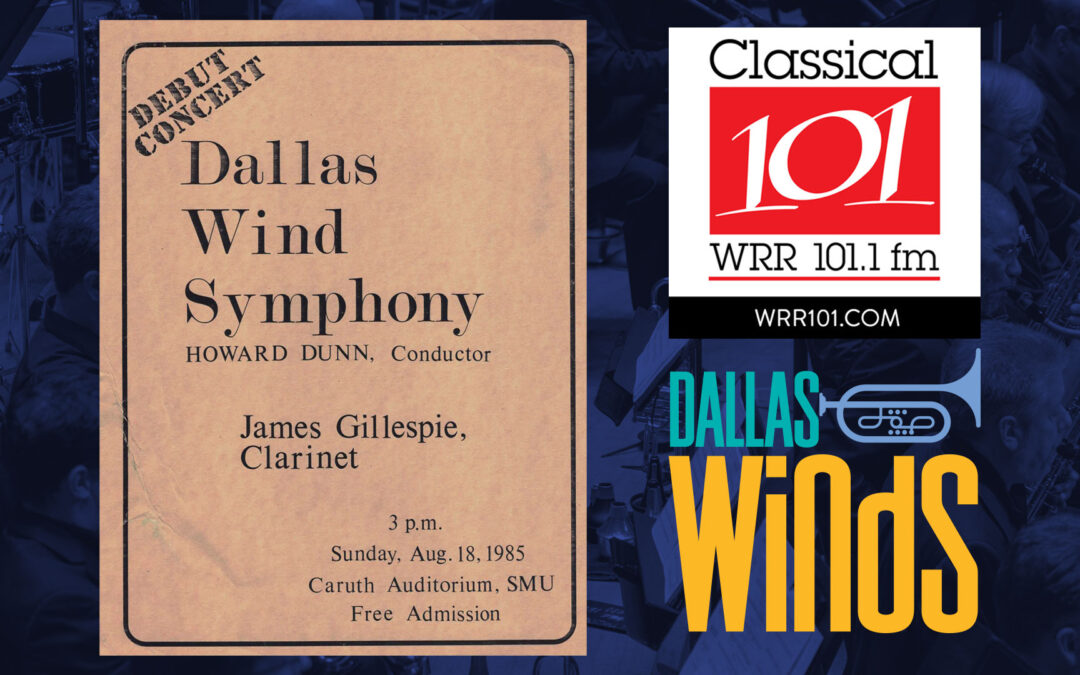

The Dallas Wind Symphony

Howard Dunn, Artistic Director and Conductor

Caruth Auditorium, Southern Methodist University

Sunday, August 18, 1985 | 3:00 p.m.

Manhattan Beach March (1893) — John Philip Sousa

First Suite in E-Flat (1909) — Gustav Holst

Concert Piece for Clarinet (1874) — Nicholai Rimsky-Korsakov

James Gillespie, clarinet soloist

The Leaves Are Falling (1963) — Warren Benson

– Intermission –

Overture to Oberon (1826) — Carl Maria von Weber

Colonial Song (1921) — Percy Grainger

Molly On The Shore (1907) — Percy Grainger

Semper Fidelis (1872) — John Philip Sousa

Symphonic Songs for Band (1957) — Robert Russell Bennett

Program Notes

Manhattan Beach, John Philip Sousa

Born: November 6, 1854, Washington D.C.

Died: March 6, 1932, Reading, Pennsylvania

John Philip Sousa was America’s first internationally acclaimed composer and conductor. By 1899, when the famed Sousa Band first toured Europe, Sousa had become “The March King,” hailed around the world as a true musical innovator. But in 1893 Sousa was still finding his way. He had left his military career behind in 1892 and spent 1893 developing a new concept for a concert band, combining immaculate musicianship with a broader repertoire and more accomplished showmanship than he could have enjoyed with the President’s Own United States Marine Band.

During that first summer, Sousa accepted an extended residency for his fledgling band at Manhattan Beach, a highly fashionable New York summer resort. He composed Manhattan Beach as a sort of theme song for the park—a musical tribute to his first high-profile gig. The Sousa Band performed this march in an unconventional way by playing the trio and last section of the march as a short descriptive piece. In this interpretation, soft clarinet arpeggios suggest the rolling ocean waves as one strolls along the beach. A band is heard in the distance. It grows louder and then fades away as the stroller continues along the beach.

First Suite in E-flat, Gustav Holst

Born: 21 September 1874, Gloucestershire, England

Died: 25 May 1934, London, England

Gustav Holst is popularly recognized as the composer of “The Planets,” however he was a very prolific composer. He composed operas, chamber, vocal, band, and orchestral music of many different styles based on subjects as varied as folk songs, Tudor music, Sanskrit literature, astrology, and contemporary poetry. His compositions for wind band, although only a small portion of his total output, have become part of the standard repertoire.

Esmail Khalili, a graduate student in music at the University of Texas—Austin, wrote in his research for his master’s degree:

Although completed in 1909, the suite didn’t receive its official premiere until 11 years later in 1920, by an ensemble of 165 musicians at the Royal Military School of Music at Kneller Hall. During this time period there was no standardized instrumentation among the British military bands, and as a result no significant literature had been previously written for the medium. Most British bands of the time performed arrangements of popular orchestral pieces. In order to ensure the suite would be accessible to as many bands as possible, Holst scored the work so that it could be played by a minimum of 19 musicians with 16 additional parts that could be added or removed without compromising the integrity of the work.

The composer states:

“As each movement is founded on the same phrase, it is requested that the suite be played right through without a break.” Indeed, the first three notes of the Chaconne are E-flat, F and C, and the first three notes of the melody when it first appears in the Intermezzo are E-flat, F, and C. In the third movement, Holst inverts the motive: The first note heard in the brilliant opening brass medley is an E-flat, but instead of rising, it descends to a D, and then a G; the exact opposite of the first two movements.

Concert Piece for Clarinet, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Born: 18 March 1844, Tikhvin, Russia

Died: 21 June 1908, Lyubensk, Russia

Rimsky-Korsakov’s best-known orchestral compositions, Capriccio Espagnol, Russian Easter Festival Overture, and the symphonic suite Scheherazade, are considered staples of the classical music repertoire. He is also recognized for his talents as an orchestrator. It is his version of Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain that has taken its place in the standard orchestral repertoire.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s three works for solo instruments and military band date from his years as inspector of the Imperial Russian Naval Bands (1873-84).

Dr. David Cannata, Associate Professor of Music History at Temple University, writes:

The composer acknowledged as much, writing in his memoirs that they were “written primarily to provide the [military band] concerts with solo pieces of a less hackneyed nature than the usual: secondly that I myself might master the virtuoso style so unfamiliar to me, with its solo and tutti, its cadences etc.” And in many ways these three pieces constitute “experiments” in that combination of ensemble sonority and solo virtuosity that earmark Scheherazade as a masterpiece of orchestral wizardry.

Although often listed as a concerto, the piece better falls under the rather nondescript title “Concertstück,” which means concert piece. The work is played without interruption (solo cadenzas provide the linking material), and movements 1 and 3 both use the same melodic material. As with the Oboe variations, the piece is testimony to Rimsky-Korsakov’s subtle mix of timbre, and from our vantage point it is difficult to see why he, dissatisfied with this work, withdrew it from performances after only a few rehearsals.

The public reaction to these works proved less than enthusiastic. Writing about the first performances Rimsky-Korsakov noted, “the soloists gained applause, but the pieces themselves went unnoticed…the audiences were still in the stage of musical development where no interest is taken in the names of composers, nor indeed in the compositions themselves: and in fact it never occurred to a good many to speculate on whether a composition had such a thing as a composer! His lifelong disappointment with the lack of interest shown in these works in performance may well explain why he never assigned them opus numbers, nor did he sanction their publication. They constitute volume 25 of the Soviet Collected Works Edition, first published in 1950.

The Leaves are Falling, Warren Benson

Born: 26 January 1924, Detroit, Michigan

Died: 6 October 2005, Rochester, New York

As composer, conductor, performer, writer and humorist, Warren Benson was perhaps best known for his dynamic music for wind ensemble and his moving song cycles. Benson wrote over 150 works, including pieces that have been heralded as masterpieces of the twentieth century. His music has been played and recorded worldwide by the Kronos Quartet, New York Choral Society, International Horn Society and United States Marine Band. Benson’s teaching career spanned over 50 years and culminated with honors including the Kilbourn Professorship for Distinguished Teaching, and appointment as University Mentor and Professor Emeritus at the Eastman School of Music.

Benson began the work on November 22, 1963, the date of the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy. Its title comes from Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem “Autumn.” The appropriateness of the imagery of falling leaves and the season of dying are obvious.

The music uses the well-known chorale Ein’ feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress), but never quotes it exactly nor uses the traditional harmonization. It is an exceptionally intense work, a sustained emotional arc over twelve minutes long. In January 1972 “The Instrumentalist Magazine” called it “one of the most significant band compositions in the last twelve years.”

Overture to Oberon, Carl Maria von Weber

18 November 1786, Eutin, Holstein

5 June 1826, London, England

Carl Maria von Weber, a cousin of Mozart’s wife Constanze, was trained as a musician from his childhood. He made a favorable impression as a pianist and then as a music director, notably in the opera houses of Prague and Dresden. Here he introduced various reforms and was a pioneer of the craft of conducting without the use of violin or keyboard instrument. As a composer he won a lasting reputation with the first important Romantic German opera, Der Freischütz.

Music critic Richard Freed writes:

Weber was in declining health when he took on the commission for his final opera, Oberon, or The Elf King’s Oath. When he left Dresden to begin rehearsals in London, he expressed a presentiment that he would die in England, and indeed he succumbed to tuberculosis there less than two months after conducting the work’s premiere. It has been suggested that he might have lived to return home if his English opera had not been such a dismal failure.

The overture, which has met with a far happier fate than the opera itself, is characterized from beginning to end by that “intoxicating sweetness.” In it Weber makes use not only of material from the opera, but also of motifs from the incidental music he wrote in 1818 for Eduard Gehe’s tragedy Heinrich IV. The same Sir Donald Francis Tovey who dismissed the libretto as “the merest twaddle” cherished the Overture as “a gorgeous masterpiece of operatic orchestration,” and many musicians have declared this last of Weber’s compositions for orchestra to be also his finest.

Colonial Song, Percy Grainger

Born: July 8, 1882 – Brighton, suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Died: February 20, 1961 – White Plains, New York

Percy Grainger was an Australian-born pianist and composer. After studying music in Frankfurt, he established himself as a piano virtuoso in England, while also pursuing other interests like collecting folk tunes in England and Denmark. He moved to the U.S. in 1914, teaching in Chicago and New York, but invested much energy in establishing an ethnomusicological center at the University of Melbourne.

Though an inveterate experimenter in the realms of timbre, rhythm, harmony, and texture, he is known for his tuneful short works for orchestra, piano, and concert band. Colonial Song was originally composed for 2 voices (soprano and tenor), harp and full orchestra. It was intended as the first in a series of “Sentimentals,” a project that for some unknown reason was never continued.

Grainger writes:

In this piece the composer has wished to express feelings aroused by thoughts of the scenery and people of his native land, Australia. It is dedicated to the composer’s mother.

No traditional tunes of any kind are made use of in this piece, in which I have wished to express feelings aroused by thoughts of the scenery and people of my native land, (Australia), and also to voice a certain kind of emotion that seems to me not untypical of native-born Colonials in general.

Perhaps it is not unnatural that people living more or less lonelily in vast virgin countries and struggling against natural and climatic hardships (rather than against the more actively and dramatically exciting counter wills of their fellow men, as I n more thickly populated lands) should run largely to that patiently yearning, inactive sentimental wistfulness that we find so touchingly expressed in much American art; for instance in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and in Stephen C. Foster’s adorable songs My Old Kentucky Home, Old Folks at Home, etc.

I have also noticed curious, almost Italian-like, musical tendencies in brass band performances and ways of singing in Australia (such as a preference for richness and intensity of tone and soulful breadth of phrasing over more subtly and sensitively varied delicacies of expression), which are also reflected here.”

Molly on the Shore, Percy Grainger

Born: July 8, 1882 – Brighton, suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Died: February 20, 1961 – White Plains, New York

In a letter to Frederick Fennell, Grainger stated, “In setting Molly on the Shore, I strove to imbue the accompanying parts that made up the harmonic texture with a melodic character not too unlike that of the underlying reel tune. Melody seems to me to provide music with initiative, whereas rhythm appears to me to exert an enslaving influence. For that reason I have tried to avoid regular rhythmic domination in my music – always excepting irregular rhythms, such as those of Gregorian Chant, which seem to me to make for freedom. Equally with melody, I prize discordant harmony, because of the emotional and compassionate sway it exerts.

Semper Fidelis March

Sousa began his musical education when he was six, and apparently settled on a musical career early; his father apprenticed him to the United States Marine Band at age thirteen to prevent young Sousa from running away to join a circus band. He served out his apprenticeship with the Marines, then joined a series of theatrical orchestras, where he learned to conduct. In 1880 he returned to the Marines to become the conductor of the “President’s Own” Marine Band, serving under five different presidents.

This march takes its title from the motto of the U.S. Marine Corps: “Semper Fidelis” is Latin for “always faithful.” The march’s trio is an extension of an earlier Sousa composition, With Steady Step, one of eight brief trumpet and drum pieces he wrote for The Trumpet and Drum (1886). It was dedicated to those who inspired it – the officers and men of the U.S. Marine Corps. In Sousa’s own words: “I wrote Semper Fidelis one night while in tears, after my comrades of the Marine Corps had sung their famous hymn at Quantico.”

Symphonic Songs for Band, Robert Russell Bennett

15 June 1894, Kansas City, Missouri

18 August 1981, New York City, New York

Kansas City native Robert Russell Bennett was Broadway’s pre-eminent arranger and orchestrator for most of his career. His ease with instruments enlivened the scores of George Gershwin, Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, and many others. He was also a successful composer, having studied with the renowned Parisian teacher Nadia Boulanger. He wrote nearly 200 original pieces for several media, including two-dozen works for wind band. The best known of these are his Suite of Old American Dances and the Symphonic Songs for Band.

Bennett wrote Symphonic Songs for Band 1957 on a commission from the National Intercollegiate Band, which premiered the piece at Salt Lake City’s Tabernacle. Subsequent early performances by the Goldman Band and the University of Michigan Symphony Band featured Bennett as guest conductor. According to George Ferencz, Bennett scholar and editor of the latest full-score edition of the piece, Bennett provided the following note for the piece’s performance with the Goldman Band:

Symphonic Songs are as much as suite of dances or scenes as songs, deriving their name from the tendency of the principal parts to sing out a fairly diatonic tune against whatever rhythm develops in the middle instruments. The Serenade has the feeling of strumming, from which the title is obtained; otherwise it bears little resemblance to the serenades of Mozart. The Spiritual may possibly strike the listener as being unsophisticated enough to justify its title, but in performance this movement sounds far simpler than it really is. The Celebration recalls an old-time country fair, with cheering throngs (in the woodwinds), a circus act or two, and the inevitable mule race.